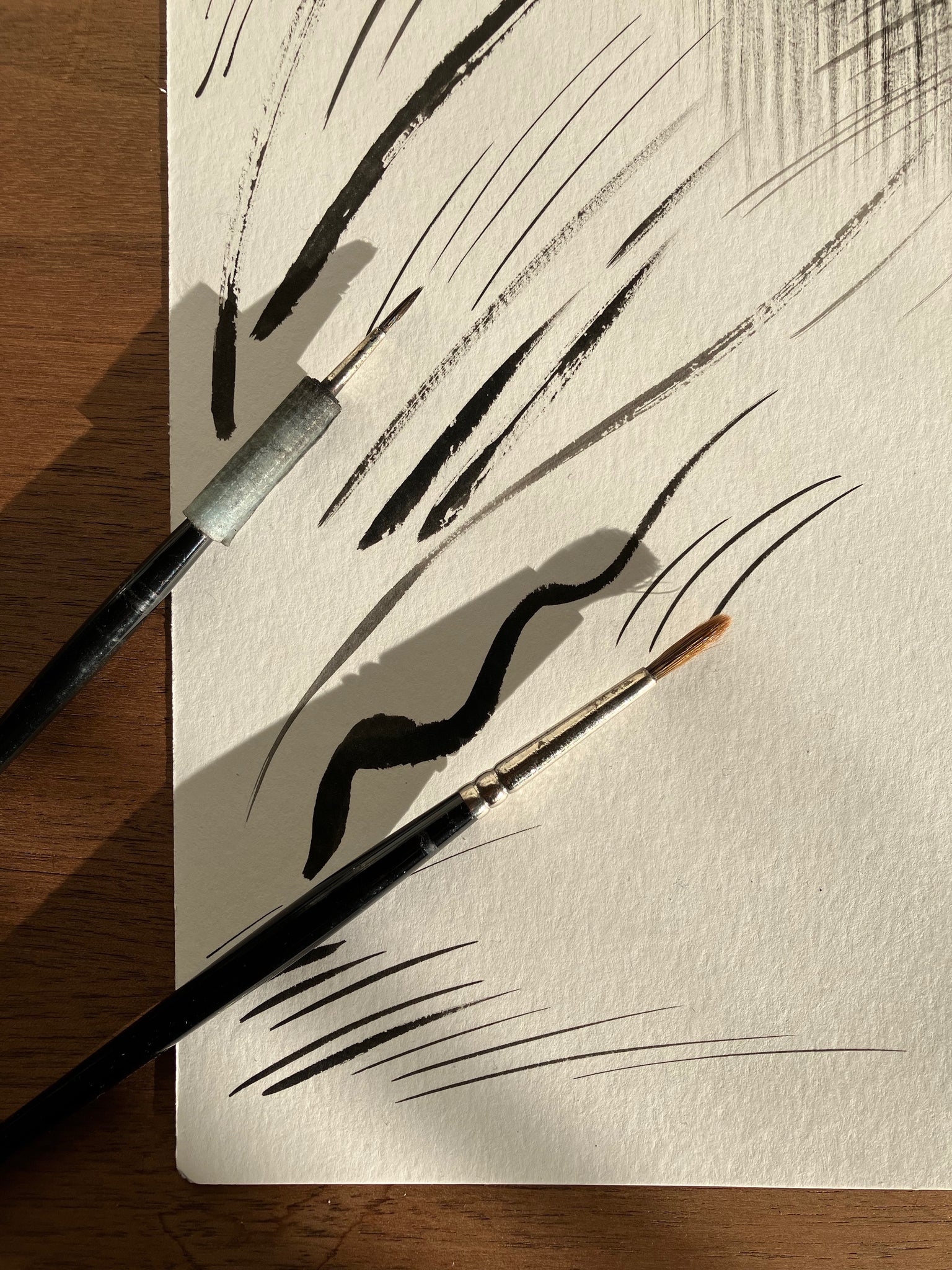

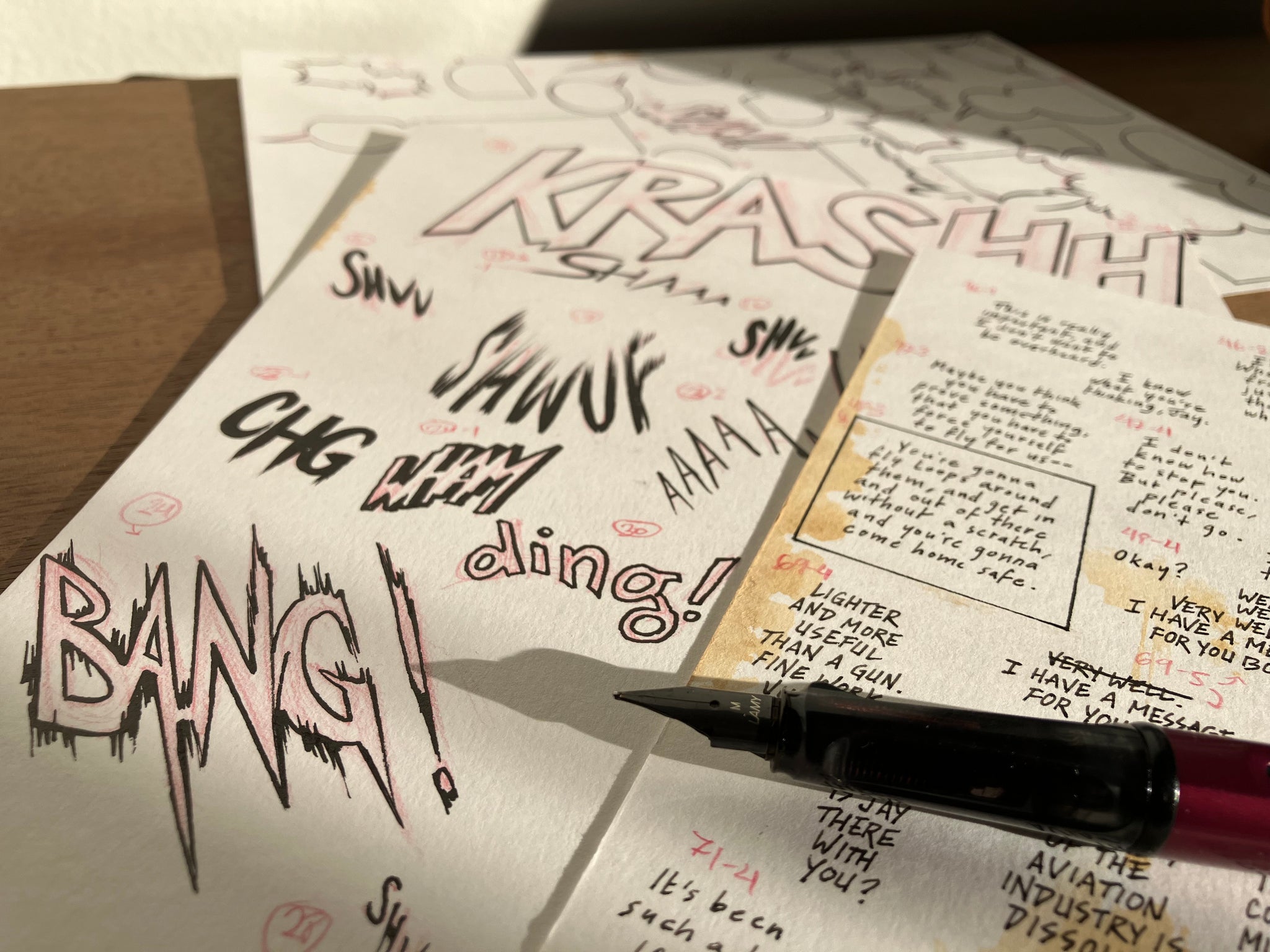

I recently took a trip to visit an art school, at the invitation of a friend of mine who is a professor teaching there. He had arranged for me to do a short lecture and live demonstration of traditional media inking. I set up at a table with my brushes and nib pen and ink and paper, then made some drawings while explaining what I was doing and thinking. We had a projector set up so the audience could see everything from their seats, but at some point my friend invited the students to gather around and watch close up. The subtle thick-to-thin strokes you can coax out of a good brush, the way freshly laid ink shines and feathers and seeps across a page before it dries matte and dark and rich, all of it is more satisfying to see without the filter of a screen. After a few minutes, the professor encouraged everyone to sit back down if they wished. Perhaps he remembered that I’d told him that in the past I’ve shaken from nerves while inking even just for a short recording. But no one sat back down. And this time, for some reason, I was perfectly calm and happy. It was probably one of my favorite experiences of live drawing ever. I think it’s because of the energy of the students, gathered around like that. It made me want to try harder, to really draw with heart.

Although I didn’t look up very often from the paper, I could sense their engagement from the questions they asked. Some were funny; all were insightful. One gave me pause.

“What do you do when you hate drawing something?”

This question haunts me because it is such a good one, and calls to mind so many others. What do you do when you can’t get past an obstacle in your practice? What do you do when the thing that brings you joy suddenly ceases to? What do you do when you feel like you’ve failed? Big questions, and you never really stop tackling them. In order to be of any help, to suggest practical exercises or inspiration and so on, I needed to get specific. I asked the student to give me an example. “What’s something you hate drawing?”

“Myself.”

“…Oh! Hmmmmm,” I said, and though I didn’t stop working I think my face must have betrayed my concern because there was a flurry of nervous laughter. It occurred to me that everyone was in the middle of their final assignment, a large self-portrait; this student could have been joking. But I didn’t think so. It didn’t sound that way. So I answered seriously.

“Well, there’s no way around it. You’ll have to draw.”

This is true regardless of whether there’s a grade at stake. If I’m drawing a comic page, and I don’t have the will to draw complicated architecture in perspective that day, I can skip that panel and focus on faces, figures, props, everything else on the page. But I’ll still have to draw that panel tomorrow. Otherwise, the full story can’t be told. I suppose my answer was not entirely accurate. There *are* ways around a drawing problem—temporary ones. Entrusting difficult tasks to a future self is one (yes, that may well be nothing more than a forgiving way of saying “procrastinate”—but constructively! Strategically!). Reconsidering the task is another (no need to draw all the buildings in detail if the silhouette of their rooftops will do). Looking closely and critically at how other people draw is still one more (the student specified that their difficulty was with some specific facial features, so I advised gathering other artists’ renderings of similar features which they *do* like, and trying out similar techniques in their own art). And of course, sometimes you just need to step away, cover the canvas, turn off the screen, talk to a friend, take a literal walk. It really is amazing how many problems shrink in size and menace after a walk.

But you’ll have to draw, eventually. Can you avoid making a drawing you hate? Can you avoid yourself? Yes, of course. But do you want to?

I believe there is something worth investigating in certain things I observe in the world. I believe in particular that I can show that “something worth investigating” to others by making pictures. That’s my hope, intention and motivation for creating art; that’s how I decide whether a drawing is a success. Hatred of a drawing, and of the self who makes drawings, comes from the disappointment and fear of falling short of that. It doesn’t help that the word “success” is so tinged with the flavor of capitalism: goal-oriented, material, printed in large capital letters under a picture of rock climbers on a motivational poster. But that’s not what I mean.

It is necessary to define what success means for yourself, otherwise others will attempt to define it for you. That goes for a career and life in general, but also for each individual sketch. I prefer the question “is this a successful drawing?” over “is this a good drawing?”, always. That’s because while good/bad describes a perceived, static value, success describes an evaluation of intention taking form. It reframes the question from “did the arrow hit the bullseye?” to “how did it fly this time, and how did I send it there?”

The lovely thing about intention is that you can see it take form and transform. And it does so with very little regard for our feelings about it. You who keep a journal know this; we don’t usually expect our own diary to be good or bad to read. But it can tell you: here’s what you were curious about. Here’s what was bothering you. Here’s you at your ugliest. Here’s you at your most sincere. Whatever you witnessed and felt stays on the page, and you can do with it what you will. For a similar reason, I told many students that day, including the one who asked this question, to keep a sketchbook (if they weren’t already doing so). In a persistent record you keep for yourself, the stress of expectation fades. It becomes less about what you can make your drawings do, and more about getting to see what the drawings are doing, left to their own devices, whether you love or hate the result—and assuming they get the chance to exist.

You’ll have to draw. But you have more time than you think, and you can try as many times as you like. Take care of yourself, and draw courageously.

—

Text and photos by: A.C. Esguerra

Where to find A.C. : instagram @blueludebar

Read other stories by A.C. : Here

Bk Artifacts Featured:

- Traveler's Notebook // Camel

- [TSL Charm] Crane

- TSL Leather Pen Roll (Photos show a previous limited edition version). Other limited editions can be found here, and here.

I cannot begin to describe how inspiring this was, thank you for sharing!

I have always wanted to having a sketchbook of my own. However, due to the fear of someone judging my artwork, I have yet to ever complete any sketchbook that I start. While I know that the odds of someone actually viewing my sketchbook are slim to none, I have let the fear take over and have stopped pursuing something I have always loved.

Thank you for encouraging me to try again and reminding me that no one is perfect!

As always, I love your insight. You are absolutely correct in the importance of defining what success means to you and not letting others tell you what it is. I’m so excited that you were able to work with these students without allowing the anxiety to overwhelm you. You have so much to offer and I’m so happy you were able to engage and enjoy the experience! :)